Pause Before You Prompt

Empowering Students to Evaluate AI Tools in a Values-Based Framework

The Important Work is a space for writing instructors at all levels—high school, college, and beyond—to share reflections about teaching writing in the era of generative AI.

This week’s post is by Maggie Boyd. Maggie works as Assistant Director for Writing Support at Boston University, where she guides the writing assistance and presentation prep programs. Previously, Maggie taught in BU’s English Department and Writing Program. Her research examines contemporary narratives of healing and she loves reading physical books. You can find her on Substack and Twitter.

If you’re interested in sharing a reflection for The Important Work, you can find information here.—Jane Rosenzweig

I often find myself in conversations about AI that range from handwringing to praise-singing. It’s rarer that I get to participate in conversations that lead to practical ideas for curating AI literacy (like those at the Babson Tea Party!). But over the last year, I’ve been lucky to team up with several librarians at my university to develop an AI literacy framework that we have transformed into an assignment and a class activity. And it has been truly fun, as well as a much-needed reminder of how much I love the deeply collaborative and dare-I-say human work of educating, learning, and writing.

Over the course of our early conversations, it became clear that using AI is an expression of values. We therefore realized that we wanted our AI literacy aid to prompt our students to consider what they value in learning and how to honor those values. So, we decided to create a values-based framework that anyone could use to help guide those decisions. First, we needed to figure out which values might be relevant for AI literacy.

As Assistant Director for Writing Support, my work running a writing tutoring program centers on the premises that writing is a meaningful endeavor, empowering us to sharpen our thinking and share it with our community, and that the act of carefully, caringly parsing our writing with another person will benefit both the writing and the writer. As we considered our values, I kept wondering: What happens when our learners could shortcut the whole process and have a machine spit out what might seem like a final product? What happens when writers could press a button to receive feedback rather than trudging across campus or even opening a Zoom and spending 45 minutes in dialogue with a tutor? What happens if students miss out on opportunities to build their confidence and capacity to communicate?

Such questions border on the existential (what’s the value of human thought or skills?) as well as the practical (what will motivate students to make appointments?). It’s evident that AI is changing the writing ecosystem. What frameworks might serve us, as educators, to better guide students to navigate that ecosystem? Our framework offers one answer, tasking students to press pause before they enter a prompt into an AI platform and ask themselves: why am I doing this?

We didn’t initially have the idea of a “pause” in our minds. We all agreed that we aspired for students to be intentional and informed about their usage, with a clear sense of their motivations and potential outcomes. We discovered along the way that pausing was a useful framing to capture this goal, especially in contrast to the emphasis on acceleration pervading AI discourse. As more tech companies push us to outsource more of our cognitive tasks, flooding the market with promises of newer and better outputs, we consider ‘pausing’ an act of resistance.

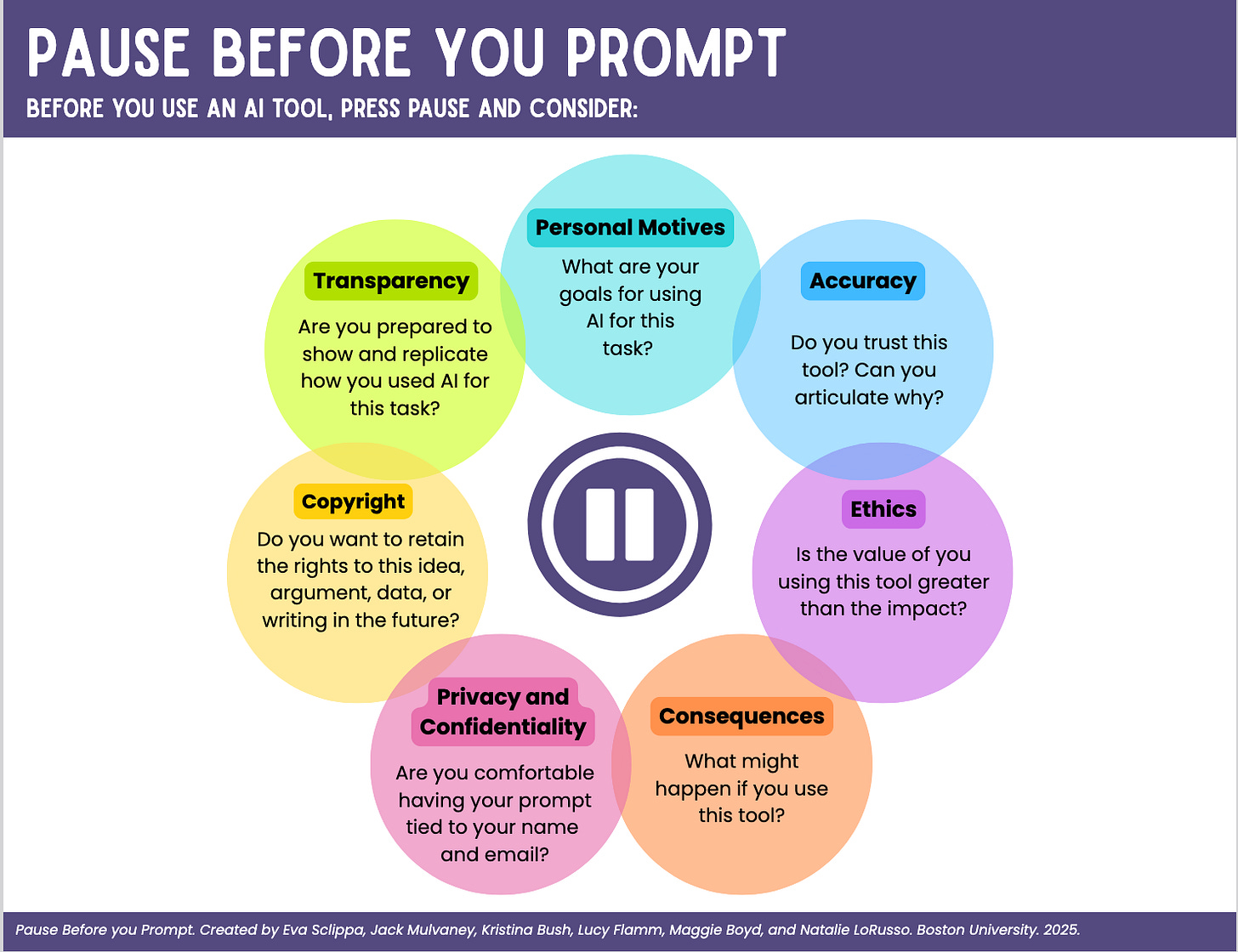

As we imagined the form of our AI literacy framework, we reviewed examples that mostly resembled decision trees (see these examples from Edutopia, Oregon State University, Memorial University at Newfoundland, University of Alberta and University of Hawaiʻi). When we met to discuss, we realized that each nexus point represented a moment of possibility: What will you do next—and why? What do you want to accomplish? What technologies will you use? What infrastructure or information do you have? We also realized that a decision tree felt too linear; we couldn’t settle on a single starting point, as each nexus felt intertwined with the next. So, we wanted multiple entry points that would all overlap, more like a decision flower.

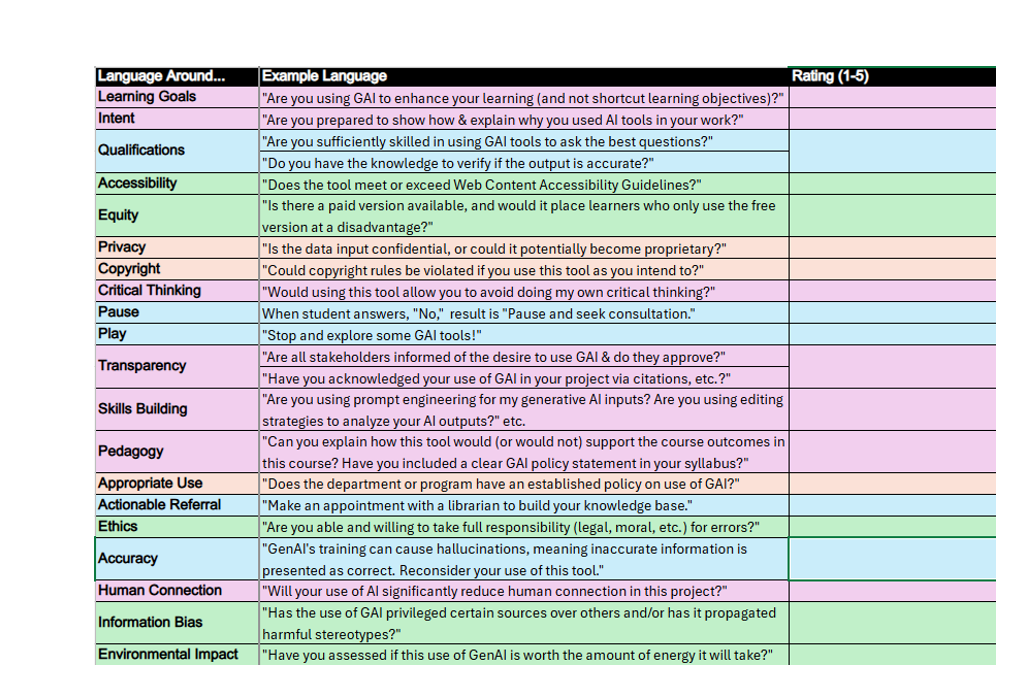

To determine which points we would include, we sorted values into broad categories that we each rated 1-5, with 1 as the most important (a sample can be found here). We added our ratings together to identify shared priorities and then used this value-assessment to decide which categories our framework would highlight.

This process proved humbling—I, for one, was surprised to find myself ranking copyright higher than equity—and fruitful. Reflecting on our own values and processes felt like we were doing the best thing we can do as educators who are responsible for guiding students to hone their own expertise: lead by example. We were thinking critically about available tools, weighing benefits against drawbacks, pruning our use cases and creating space to reflect.

From there, we felt ready to formulate our thinking into a framework that would center the seven considerations we had collected. After some experimentation, we ended up with our decision flower, “Pause Before You Prompt,” available in condensed and expanded versions at bit.ly/ai-pause.

With this framework, we aim for students to reflect on which considerations (or petals) most align with their values and start asking themselves questions like the ones we pose. By creating this opportunity for value-assessment, we hope to empower students to visualize how AI would or would not benefit their academic experience and what might be lost in the process. We want students to maintain agency over their learning, rather than treating AI tools flatly as exterior co-writers.

Soon after we started sharing our framework, we heard from faculty and staff that it propelled productive discussions in their classrooms and meetings. I was excited to try it out in my own context in the writing center, where I have been feeling the pressure to adapt to an AI landscape. I’m not the only one—in fact, a recent report on generative AI in writing centers, tellingly titled “The Burden of GenAI Has Increased, and the Mood Has Turned Sour,” showcased the widespread sense from writing center staff that our programs will need to adjust our practices to address AI. It hardly astonished me to see that many of us dedicated to students’ writing are seeing more work and less hope. But, with our framework in hand, I felt much more equipped to make one such adjustment and train our tutors on AI literacy.

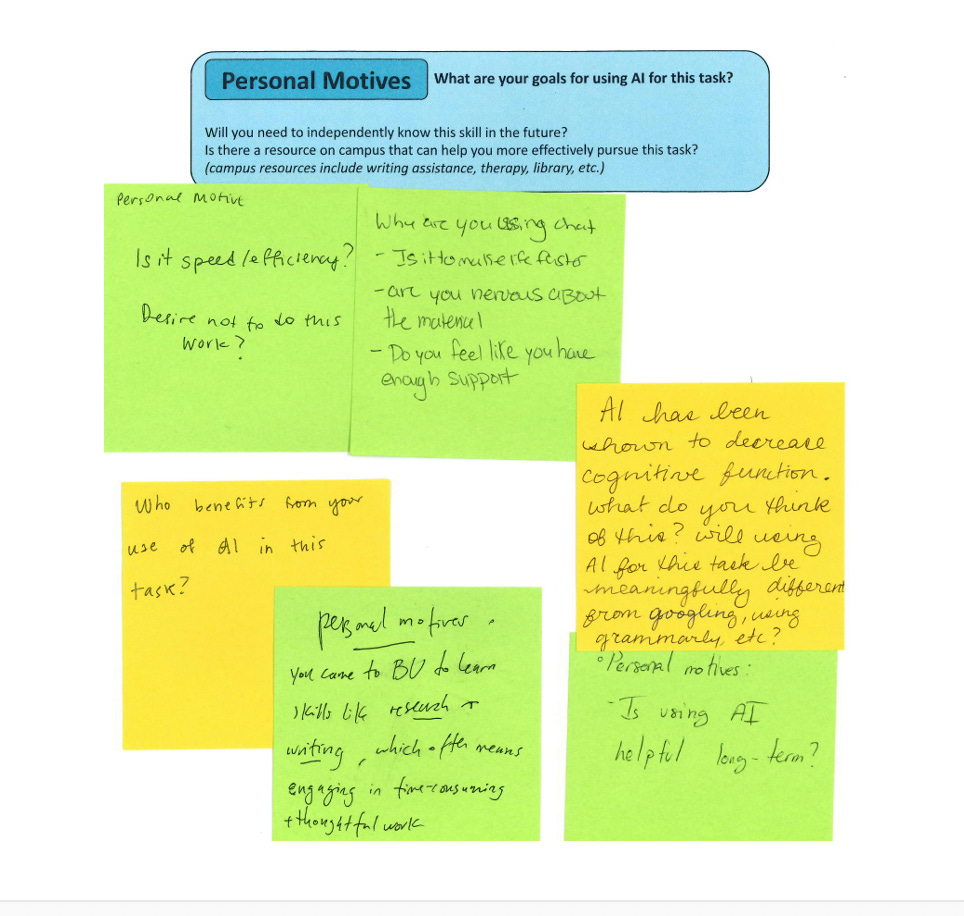

To initiate dialogues around AI usage among our tutors, I integrated our framework into a tutor training activity. I distributed papers around the room, with each sheet dedicated to one “petal,” featuring the topic and the sub-questions. I gave each tutor sticky notes and tasked them with moving around the room, adding one note per sheet with either a strategy for addressing an existing sub-question or an additional sub-question that they would ask a student. I wanted to spark a conversation about how our tutors might shepherd students to be more intentional and informed when considering GenAI usage—and I think we succeeded. Tutors leapt into the discussion, sharing student questions from previous sessions (many now worry about using an em dash, for example), mentioning their own suggestions (reviewing the academic policies that require students to cite AI, for another example) and bonding over frustrations.

Under “Personal Motives,” the sticky notes read →

“Is it speed/efficiency? Desire not to do this work?”

“Why are you using chat - is it to make life faster? Are you nervous about the material? Do you feel like you have enough support?”

“AI has been shown to decrease cognitive function. What do you think of this? Will using AI for this task be meaningfully different from googling, using Grammarly, etc.?”

“Who benefits from your use of AI in this task?”

“You came to BU to learn skills like research + writing, which often means engaging in time-consuming thoughtful work”

“Is using AI helpful long-term?”

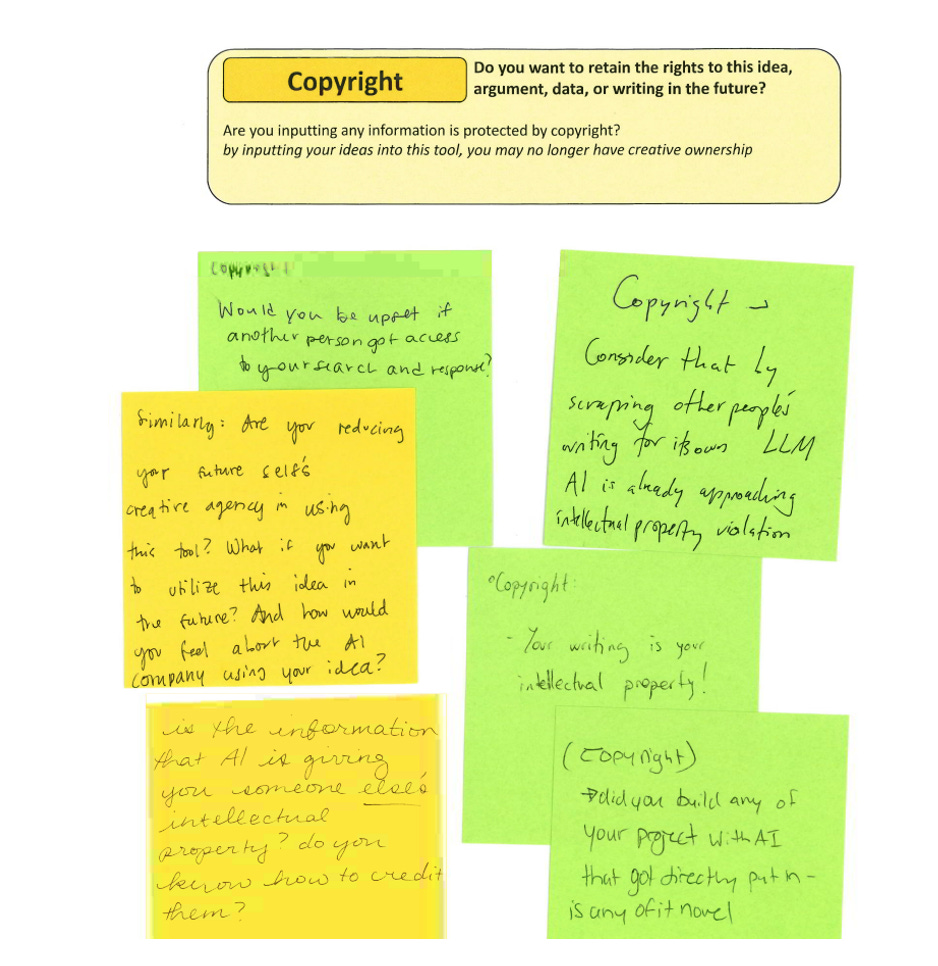

Under “Copyright,” the sticky notes read →

“Would you be upset if another person got access to your search and response?”

“Consider that by scraping other people’s writing for its own LLM, AI is already approaching intellectual property violation.”

“Are you reducing your future self’s creative agency in using this tool? What if you want to utilize this idea in the future? And how would you feel about the AI company using your idea?”

“Your writing is your intellectual property!”

“Is the information that AI is giving you someone else’s intellectual property? Do you know how to credit them?”

“Did you build any of your project with AI that got directly put in? Is any of it novel?”

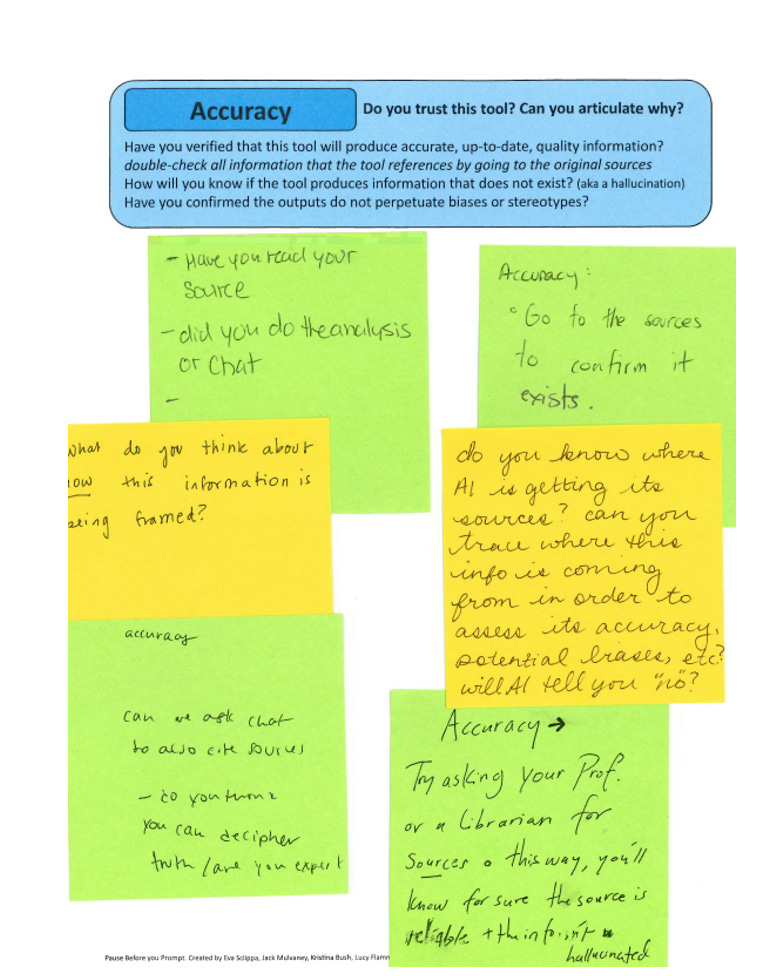

Under “Accuracy,” the sticky notes read →

“Have you read your source? Did you do the analysis or chat?

“Go to the sources to confirm it exists.”

“What do you think about how this information is being framed?”

“Do you know where AI is getting its sources? Can you trace where this info is coming from in order to assess its accuracy, potential biases, etc.? Will AI tell you no?”

“Can we ask chat to also cite sources? Do you think you can decipher the truth / are you an expert?”

“Try asking your prof or a librarian for sources—this way you’ll know for sure the source is reliable and the info isn’t hallucinated”

“Will AI tell you no?”

This sampling shows how the writing tutors are contemplating what AI allows and especially what it forecloses. They are full of questions, focused on the larger writing ecosystem: the other sources that AI trains on, the professors who will read this work, the future possibilities of a given project and student, etc. One asks a striking question: “Will AI tell you no?” If AI always gives you what you ask for, how will you learn what you don’t know to ask for, or what you don’t want to hear but would actually strengthen your work? Human collaborators can push back or re-orient or, we might say, press pause—an essential ingredient of thinking, researching and writing.

Whether a librarian, writing center admin or peer tutor, we are all feeling the pressure to be prepared to shepherd students to make smart decisions about if and how to use AI. Across early experiences, our framework has provided an engine for kindling that type of careful, critical work. Talk about generative.

You are welcome to use any of the materials shared here!

Collaborators on this project included Kristina Bush, Lucy Flamm, Natalie LoRusso, Jack Mulvaney and Eva Sclippa.

For their final exam, my first-year writing students are creating personal values statements about their use of GenAI. This is just what I needed to read (and share with them) today!

This framework is an impressive, thoughtful approach. Empowering students to use AI intentionally while maintaining agency over their learning.

I talk about the latest AI trends and insights. If you’re interested in practical strategies for using AI thoughtfully in learning, writing, and personal development, check out my Substack. I’m sure you’ll find it very relevant and relatable.