Reading With a Custom GPT

The devil is in the details

The Important Work is a space for writing instructors at all levels—high school, college, and beyond—to share reflections about teaching writing in the era of generative AI. We hope to spark conversations and share ideas about the challenges ahead, both through regular posts and through comments on these posts. If you have comments, questions, or just want to start a conversation about this week’s post, please do so in the comments at the end of the post.

This week’s post is by Stephen Fitzpatrick, who is the Director of Debate at Hackley School in Tarrytown, New York, where he has taught history in both the middle and the upper school since 1995. During his tenure at Hackley, Mr. Fitzpatrick served as the Director of Curriculum for the Middle School and for the past thirteen years has worked closely with both the Public Debate Program and English Speaking Union promoting and organizing professional development workshops, run tournaments, and outreach programs designed to expand debate and debate instruction into schools and classrooms in the tri-state area. In 2023, Mr. Fitzpatrick was awarded a grant through his school to pursue a deep interest in generative AI and its implications for education. He shared his views with the Hackley community which you can read here. You can also find him on LinkedIn.

If you’re interested in sharing a reflection for The Important Work, you can find all the information here. —Jane Rosenzweig

Last month, I experimented with my high school sophomores in my American History classes at the independent school where I teach. I created a custom GPT using a chapter from our history textbook as the source material along with specific instructions to help the user navigate the major themes, issues, details, and other aspects of the Market Revolution (see the custom instructions here).

After I explained the assignment and demonstrated how to use the GPT, I gave students premade questions to help understand the material (see the assignment which includes the link to the Custom GPT here). I told my students I had two goals for them: “First and foremost, I want you to understand the critical changes which occurred during the time period known as the Market Revolution (c. 1800 - 1840) and to familiarize yourself with its key facts and details. Second, I want to introduce how AI can deepen your engagement with historical content by enhancing the ways you interact with and understand it.”

Like many schools, our approach to AI has mostly been “don’t use it.” Most issues with generative AI involve plagiarism —students submitting AI text as their own. My reading assignment demonstrated a different way to use AI. By attaching the text to the Custom GPT and asking students to read it ahead of time, I attempted to provide a way for them to leverage AI’s ability to interact with text using targeted prompts.

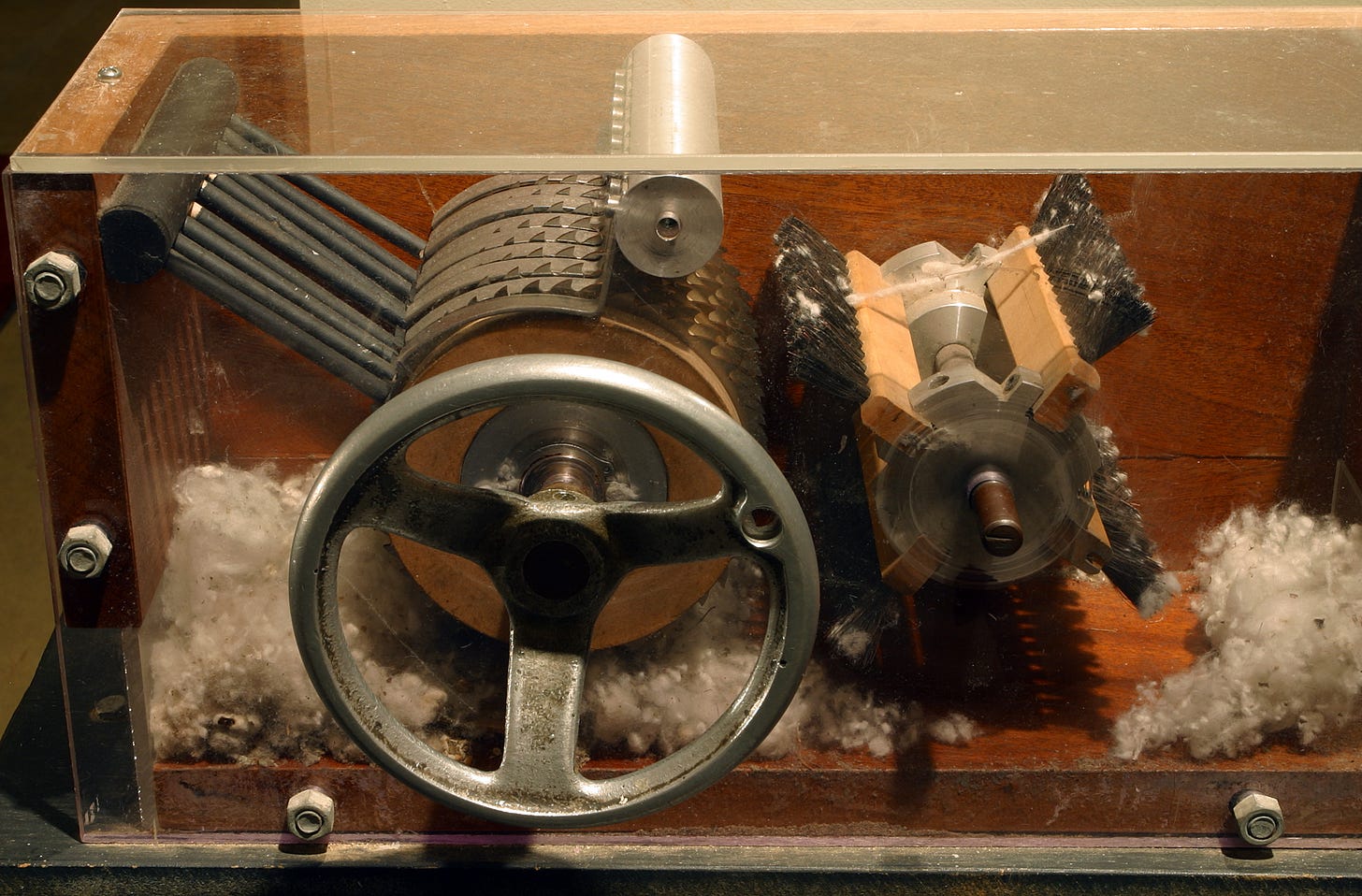

For the next 45 minutes, students could use ChatGPT in a way most had not done before. I walked around the classroom answering questions, clarifying aspects of the assignment, and observing how students approached the guided questions and wrote their own prompts to elicit information and connections within the text. Along with the chapter, I had provided images, graphs, maps, and period artwork which they could analyze with AI. Most students hadn’t experimented with AI’s multi-modal capabilities to detect and interpret images. Within the assignment were examples of how targeted prompts could help clarify and connect ideas, especially with graphs, maps, and charts.

As part of the exercise, students were asked to complete reflection questions detailing their experience. Responses varied, but several themes emerged. Not all students felt the AI was more helpful or useful than re-reading the original text, yet many saw the potential for AI to help with understanding. One student noted, "I think it did help me because I was able to go deeper into the topics that interested me and it also gave me some new or more in-depth ideas than the textbook."

The key observation for students who found it useful was the recognition that the quality of their prompts mattered significantly. One student reflected, "I felt that making sure the question that I was asking was clear enough for AI to understand was a key aspect of making sure the answer I got was what I was looking for." Another added, "I asked the AI about specific prompts and how they are relevant to my topic. I also found that asking follow-up questions was very effective in clarifying context." Through trial and error, students who integrated their understanding and crafted thoughtful questions got more out of the AI than those who didn't master that technique.

One student's reflection showed a shifting perspective. He observed, "As I said in class, which may have come as a surprise to you, this was genuinely my first time ever using a generative AI like this. It has really surprised me and I think that it has definitely changed my opinion on it, as now I've found that there are ways to use it while also critically thinking by yourself."

Interestingly, none of the students who questioned the value of using AI in this way classified it as “cheating.” My primary motivation for creating this activity was because I sense the current obsession with AI in schools is fixated on a narrow issue—AI submitted text. Plagiarism is not only difficult to prove but something students will figure out how to get around. If it isn’t already, student use of “undetectable” AI will become the norm. Students will continue to use AI regardless of whether we want them to or not. If teachers are to maintain credibility with students, it’s essential to demonstrate how and why AI use might be beneficial while at the same time acknowledging the risks. Some schools are experimenting with using AI to brainstorm, outline, give feedback, and theoretically augment the learning process. As a result, many teachers and professors in K-12 and college are finding different ways to incorporate and leverage AI in their classrooms.

Quite a few observers, both within and outside education, have questioned these practices. They legitimately ask whether off-loading cognitive tasks to AI may short circuit and inhibit rather than enhance learning. “Deskilling” is a very real fear if future generations of students don’t routinely exercise critical thinking skills. My own feeling is that, like many debates, the actual situation is more nuanced than the simple binary of “no student use of AI vs. lots of student use of AI.” The problem is compounded by the fact that teachers and students did not ask for these tools. Generative AI has subjected us to a real-time “experiment” we were entirely unprepared for. That, along with the speed with which generative AI is improving, will only make the situation more complex.

I’ve done other AI experiments in my high school classes, notably in an Independent Research class for juniors and seniors. However, I’m wary of its impact on student learning and see both sides of the issue. Recent National Assessment of Educational Progress test scores reveal young people’s reading skills are atrophying. I’m aware many students may use AI to summarize and “complete” assignments by generating an interactive “Cliffs Notes” version of complicated or “boring” texts. Using AI to read Shakespeare would be sacrilegious but using AI to analyze language in Shakespeare might be interesting. It’s a slippery slope.

The Catch-22 is that students need to read and write well in the first place in order to use generative AI tools effectively. I fear AI will widen the educational divide rather than bridge it as the tech evangelicals would have us believe. Tools like Google’s Notebook LM (which generates realistic “podcasts” from uploaded documents - I created one on the Market Revolution you can listen to here) offer tantalizing possibilities for creating supplemental materials while Deep Research models (recently released from Google and OpenAI) create an existential crisis for teachers assigning research papers.

My experiment with a custom GPT to assist with reading a textbook chapter reinforces what I think most educators already know - technology, whether the internet or AI - is not inherently good or bad. The devil is in the details. Going forward, my mantra is to ask whether the benefits outweigh the harms for each use case. The difficulty is in making that evaluation.

Great piece. I hope the freedom to experiment with AI tools becomes more common. Such a better response than requiring teachers to attend webinars and workshops telling them what not to do, or worse, imposing particular AI products.

Thank you so much for writing this up – it's brilliant! Any chance you could describe a little bit more about the other "supplemental materials" you fed the GPT in addition to the book chapter? Also, I imagine there were some students who did the reading ahead of time more thoroughly than others... Did students who prepared less well have a more difficult time with the activity? Thanks again!