What are students using AI for?

And what do their answers suggest about what they need from us as teachers?

Welcome to the first of what we hope will be many posts about teaching writing in the age of AI! The Important Work is a space for writing instructors at all levels—high school, college, and beyond—to share reflections about teaching writing in the era of generative AI. We hope to spark conversations and share ideas about the challenges ahead, both through regular posts and through comments on these posts.

Our first post is by Spencer Lane Jones, a writer and teacher currently pursuing an MFA in the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa. She is writing a book about how four extraordinary schoolteachers in Europe confronted the profound social and political crises of the early 20th century. She writes "In the Schoolhouse" on Substack, and you can find her on X and BlueSky.

If you’re interested in sharing a reflection for The Important Work, you can find all the information here. —Jane Rosenzweig

In May 2023, at the end of the semester that saw the advent of ChatGPT on school campuses nationwide, I distributed a supplemental end-of-course survey to my students. I teach Introduction to Rhetoric to primarily first-year undergraduates at the University of Iowa, where I will finish my MFA in the Nonfiction Writing Program this May.

I gave a rationale for the additional survey questions.

“Artificial intelligence is part of our world now,” I said. “You are learning how to operate as a university student in that world, and I am learning how to adapt as a teacher. I’d like to know how many of you used ChatGPT in Rhetoric and, if you did use it, what specifically you used it for.”

Like many instructors in my department, I’d issued a blanket taboo on AI use in the syllabus at the beginning of the semester, and I was not ready or willing to use it as any kind of “teaching tool.”

I assured my students that the survey questions were meant for my own awareness, not for last minute surveillance or punishment. Grades were done. I hadn’t suspected that any student had used ChatGPT to generate an entire paper or speech.1

I distributed the same survey (with minor question edits) at the end of Fall 2023, Spring 2024, and Fall 2024.

Below are some of the results2:

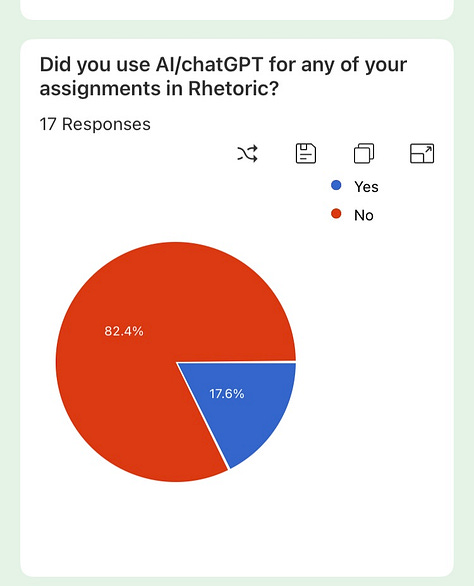

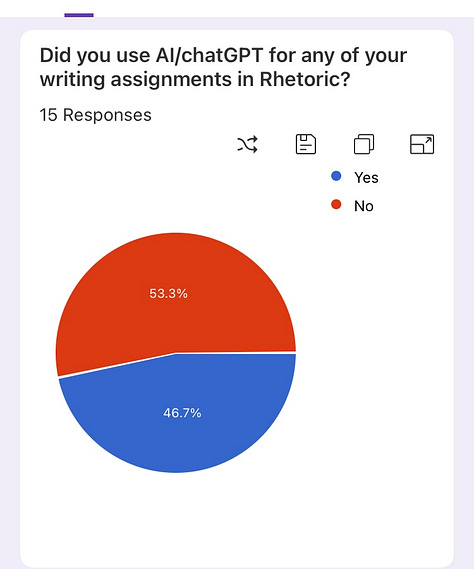

Survey Question: “Did you use AI/ChatGPT for any of your assignments (minor or major) in Rhetoric?”

Key takeaways from this data set:

In every section, a minority of respondents said they used ChatGPT, but in two sections that minority was slim. No section showed 0% ChatGPT use.

There are wide variations that cannot be explained by survey data alone. My syllabus did not radically change across semesters. Nor did my scoring rubrics. I taught the same books with essentially the same pedagogy. What explains students’ varying levels of comfort and risk with AI for academic work, especially across sections I taught in the same semester? For example, the bottom-right and bottom-center graphs show markedly different responses, but I taught both sections in Spring ‘23.

There aren’t enormous differences in academic success across these sections, and the sections with higher usage don’t necessarily show more success grade-wise. In the section where students used ChatGPT least (bottom-right), among students who passed the course, the average final grade was an 87.16%. In the section where students used it most (top-left), among students who passed the course, the average final grade was an 88.56%. Interestingly, the bottom-center pie belongs to a section that had an 84% average, a third of a letter grade below the bottom-right section, which used ChatGPT much less.

After the blunt yes/no question, I asked two follow-up questions that required short-form responses:

“If you answered yes, for which assignments?”

“If you used AI, how/why did you use it? (For help with grammar? Writing with quotes/sources? Help with explanations?)”

Here are some themes that emerged from the responses:

Generating Writing

No one turned in a paper that reeked fully of robot. 10 respondents said they used ChatGPT for an unspecified amount of help on the rhetorical analysis paper. 12 respondents said the same for the research paper. 2 respondents said they used ChatGPT to generate an unspecified amount of content for at least one major speech.

A significant number of respondents noted that they used ChatGPT in the “Ground Zero” stage of their papers. In short, many students who used it did so to avoid the inherent clumsiness or messiness of beginnings–beginnings of each paper, of particular paragraphs, of transitions, etc. Some highlights:

“It's hard sometimes to start an essay or any writing assignment—I used AI to help me get inspiration on what to write in the beginning and took it from there.”

“If I was trying to say something and didn't know how to say it I would ask for suggestions.”

“I used it to give me ideas on points to include in my paper.”

“I think ChatGPT can be really helpful to get ideas for your paper and to get your brain pumping. But I don’t think these should be used to ever WRITE a paper. That’s just boring.” [Several of the responses show similar thoughts–students trying to ethically reason through acceptable/unacceptable uses of AI, regardless of the ban I’d laid out in my syllabus.]

“I used it to help me get ideas. I couldn't figure out what else to write.”

“I used it to help give me some sentence starters and ideas on topic sentences. I never used it to write my entire essay or do all my homework. I think AI in moderation is very helpful. You learn nothing if you do not try at all. But if there is a new tool that can help me and benefit me and my grades? It is only going to get better and become part of our daily lives. Why not try and understand it before it's too late? I know plenty of students and friends who use it.”

Mechanics: Grammar & Citations

~8 students said they used AI for help with grammar, implying that they used it as a copyeditor. ~3 said they used it for help generating citations. These respondents noted that they felt there was a sharp difference between using AI as a corrector and using it as a generator.

“Primarily it was Grammarly for spelling, grammar, the works. As for other AI, in some classes I'd use it to help me clarify prompts or questions on out-of-class work. So in short, nothing that's morally unethical; nothing that'd have my work be anything but wholly my own.”

“If I had a sentence that wasn't flowing like I wanted it to, or had a grammatical error I wasn't catching, I would ask AI for help and then adjust accordingly. I didn't use it for anything major.”

Scoring & Feedback

~6 students said they fed their paper and the scoring rubric into ChatGPT and used it to generative feedback on their work. I’m no expert, but apparently ChatGPT is pretty good at this. Beginning in Spring 2024, I told my students that this kind of use was acceptable. I don’t grade first drafts, so I told them it might be worth their time and attention to get feedback from ChatGPT and then bring the results to me to discuss. “It’s good, but not great, and certainly not perfect,” I said. “And ultimately, a robot doesn’t put your grade into the book. I do.” I insisted that no matter what AI told them about their work, they should run the feedback by me first. Only one person did.

Readings & Discussion Posts

To me, this was perhaps the most concerning set of responses.

I teach two books in Rhetoric: Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985) and Brooke Gladstone’s The Influencing Machine (2011). We read each book slowly, in six or seven chunks. After each reading chunk, students write discussion posts that serve several purposes: 1) They solidify and demonstrate students’ comprehension of the texts, 2) They give me an opportunity to flag errors or misunderstandings in students’ reading so those misunderstandings don’t trickle into a major paper, and 3) They help students target and respond to the books’ main arguments and prepare for substantive seminar discussions in class.

The short-form survey responses suggest that students are using AI to read for them as much as, if not more than, they are using it to write for them. This is a particular phenomenon that may not yet be getting the attention it deserves in mainstream media.

Several students used AI to “summarize” chapters from the books or “clarify” their major points. Some students used ChatGPT to “re-word” or “explain” the discussion post prompts (which were written by me).

“If I was a little confused about what one of the Postman questions was asking I found it helpful to put in the question and ask for it to be re-worded or something.”

“For Postman I would have it help summarize and explain chapters, as well as help with discussion questions (not just having it answer for me, but help explain what Postman was getting at in certain parts).”

“I used it to understand the chapters more because some of the chapters were hard to read.”

And a smaller number of students used AI to generate responses to the discussion post prompts for them.

“I used it to answer some of the questions I didn’t know.”

This shouldn’t be surprising. There’s been a flurry of reporting over the past few months about books declining on college syllabi due to students’ struggles to read them, shrinking numbers of children and adolescents reading for pleasure here and in the UK, and writing from educators on Substack about whether we should keep up the Fight for Full-Length Books, and the extent to which schools as institutions are preserving teachers’ capacities to do so.

Reflections

I’m concerned about students trading coming to office hours (admittedly more time-consuming, intellectually rigorous, and socially awkward) for the convenience of outsourcing reading to a machine.

To keep up The Important Work, teachers at all levels will have to ensure our classroom practices encourage students to take more risks; the writer’s Risk of the Blank Page and the reader’s Risk of the Complex Book. Learning almost always rewards grappling with messiness, but grade books rarely do, a problem that long preceded the advent of AI.

How should we adapt? Where to start? Certainly not all hope is lost. Few students who are truly uninterested in learning come to college.

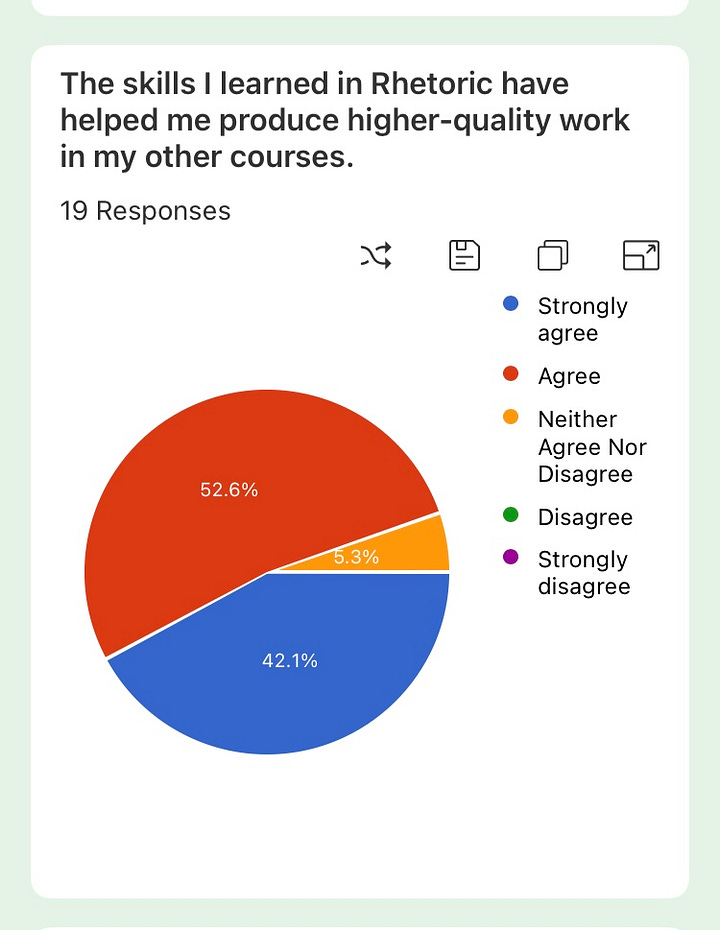

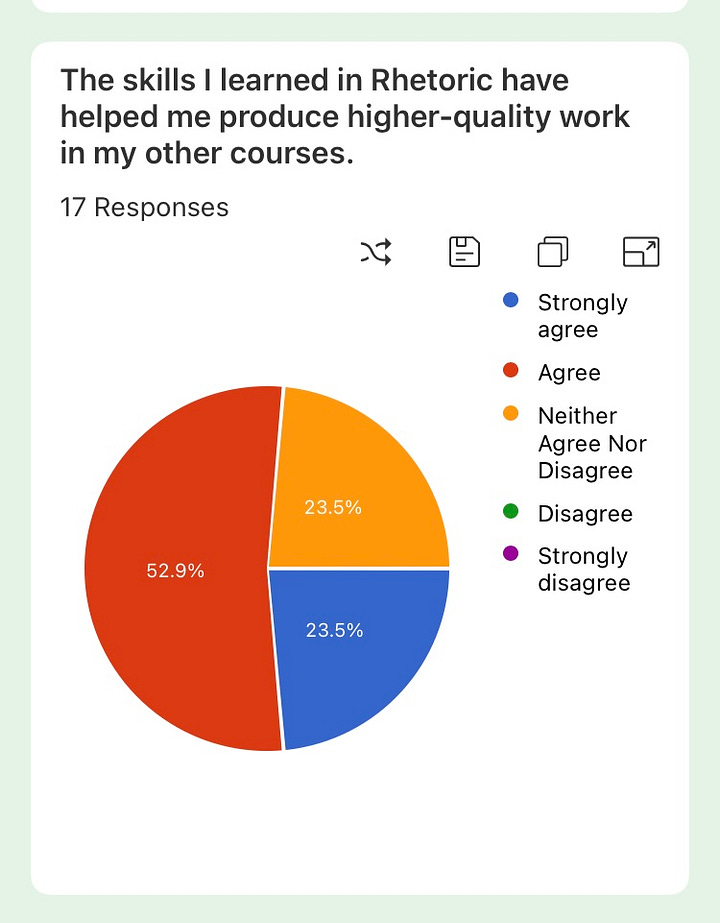

On the same end-of-course survey, in Fall 2023, Spring 2024, and Fall 2024, I asked students to rate their agreement with the following statement: “The skills I learned in Rhetoric have helped me produce higher-quality work in my other courses.”3

Survey Question: “The skills I learned in Rhetoric have helped me produce higher-quality work in my other courses.”

Most students agreed.

The question is not, “How do we convince our students that reading and writing are valuable enterprises?” The question is: “How do we teach our students how to live more fully and earnestly into the all-too-human challenges that readers and writers necessarily encounter?”

If you’re an instructor with tools, strategies, and/or resources for these challenges, leave us a comment below!

1 Introduction to Rhetoric is a required course for all undergraduates at the University of Iowa. In RHET 1030, students write two papers–one rhetorical analysis paper and one research paper–and give two formal presentations. Since Fall 2022, I have taught six sections of RHET 1030 and one section of RHET 1060, in which students have tested out of the writing requirements and give three major presentations instead. Since ChatGPT was not available to students in Fall 2022, that section is not represented in this post’s data.

2 Sections of RHET are capped at 20 students. The combined data here represents 101 responses from 120 students total who entered the course. That’s an 84.17% response rate. Some students withdrew before the end of the course. A few had already failed and thus withdrawn before the end. A few chose not to respond to the survey.

3 I didn’t think to ask this question in Fall 2023, though I’ve asked every semester: “Do you think that Rhetoric should be a required course?” Every semester, a majority of students have said yes.

100% yes on the "students are using generative AI as part of/in lieu of doing complex reading." I've got a student in AP US History who started the semester totally bamboozled by the textbook, which was a major roadblock for him. Clearly he'd never had significant reading expectations prior to this, and the book was a major ramp-up that he didn't know how to address, which led to panic, magical thinking, and a lot of bargaining with himself. He admitted later to a strategy of feeding chapters through ChapGPT (he had to come up with a workaround given the copyright restrictions on the e-text), and then studying the results. We've had a lot of discussions about this - lots of ex post facto justifications, most of which I've shot down - but on the other side, he's mostly judging the attempt unfavorably because it wound up being more time-consuming than he had expected, not on any other basis. It's the wild west out there right now, and we're playing whack-a-mole, to wildly mix the metaphor.

It concerns me that students didn't apparently understand that entering someone else's book, or any intellectual property, into Chat GPT without explicit permission is intellectual theft. Did you discuss this point? Not all writers want their books chopped into AI slop. I don't. Would they consent to having their work chopped up and given away? Seems like a teachable moment.

Also seems like a moment to discuss the value of originality, critical and creative thinking. You might find this series of posts on originality relevant:

https://open.substack.com/pub/janetsalmons/p/encourage-originality-create-a-culture?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=410aa5