“ChatGPT, can you revise this draft in the style of a scientific paper?”

Formalizing and deformalizing academic writing–with and without AI tools

The Important Work is a space for writing instructors at all levels—high school, college, and beyond—to share reflections about teaching writing in the era of generative AI.

This week’s post is by Stephen Heard, who is Honorary Research Professor at the University of New Brunswick, in Fredericton, NB, Canada. He is an evolutionary ecologist who thinks a lot about scientific writing—how we do it, and how we teach it. He is the author of The Scientist's Guide to Writing and coauthor of Teaching and Mentoring Writers in the Sciences, and he blogs at Scientist Sees Squirrel.

If you’re interested in sharing a reflection for The Important Work, you can find information here.—Jane Rosenzweig

“Write up your results in the style of a scientific paper.”

Untold thousands of undergraduate science students have received that instruction, and it’s done a lot of damage to our professional literature. These days, AI writing tools may be making the problem even worse—although with good instruction, they could offer solutions instead. Puzzled? Let me explain.

Like any writing genre, scientific writing has conventions of format and style, which science students need to learn so that they can produce writing that meets reader expectations. Some of those conventions are extremely helpful, like the “IMRaD” (“Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion”) system of organization that helps writers structure a paper and helps readers locate information in one. Other conventions are productive in moderation but are often taken too far, like the use of technical terminology to communicate with precision—or, less happily, to bewilder and tangle an unsuspecting reader in impenetrable thickets of jargon. Still other conventions are simply unfortunate relics of past bad decisions—like many scientists’ lingering insistence on the passive voice.

The tricky reality of these conventions is that science students seldom learn them via formal instruction. Full courses in scientific writing are unusual, and required courses that come early in a university career are truly rare. Instead, things typically play out like this: instructors ask students, usually in a 1st or 2nd year undergraduate course, to write up laboratory results “in the style of a scientific paper.” Unsurprisingly, they aren’t sure what that means, and so instructors may offer them follow-up advice: “go to the library, read some scientific papers, and write like that.”

And therein lies the problem. The scientific literature our students find largely consists of papers that are tedious and turgid, bloated with complex sentences, festooned with acronyms, and written doggedly in the third person and the passive voice. So that’s what they write, and that’s what we (too often) reward them for writing —all the while groaning about having to read it. Later in their careers, many of those same students add their own papers to the published literature—papers that reflect what they learned from imitating what was already there. The feedback loop continues, with the next generation of students finding yet more tedious and turgid papers to imitate in their turn.

Perhaps I’m painting this too darkly. There are, after all, folks fighting the good fight: arguing that academic writing can be both professional and engaging. Consider, for example, Anne Greene’s Writing Science in Plain English, Helen Sword’s Stylish Academic Writing, or even my own book, The Scientist’s Guide to Writing. There are instructors using those resources and others to encourage developing writers to do better than what they see in the literature. But it’s an uphill battle, because the feedback loop is powerful. And sadly, the sudden availability of AI writing tools (LLMs) has made the uphill steeper.

Whatever institutional or course-level policies might say, many students have adopted LLM tools —some with enthusiasm, some with reluctance. My informal surveys of graduate students in the sciences suggest that at least 80% of those students use LLMs in some way; among undergraduates, a recent survey at MIT found 46% of undergraduates use LLMs daily and most use them at least occasionally. Some of those uses are disturbing (“ChatGPT, please write this paper for me”); others suggest promising ways to harness new technology for learning (“ChatGPT, I’m not a native English speaker. Can you help me polish the grammar in this draft?”). But one use I’ve seen is directly relevant to this column: “ChatGPT, can you revise this draft in the style of a scientific paper?”

Students are understandably eager to find help formalizing their writing and conforming with genre conventions. After all, even when they aren’t taught those conventions explicitly, they know that they’ll be evaluated on their success in deploying them. And in asking LLMs for help in reproducing the style of a scientific paper, they’re (perhaps accidentally) using those tools in exactly the way they’re designed to excel: producing text that sounds like a human writer (of a particular genre) produced it. Sure enough: if you feed a draft text into ChatGPT and ask for a revision in the style of a scientific paper, that’s what you’ll get. In spades!

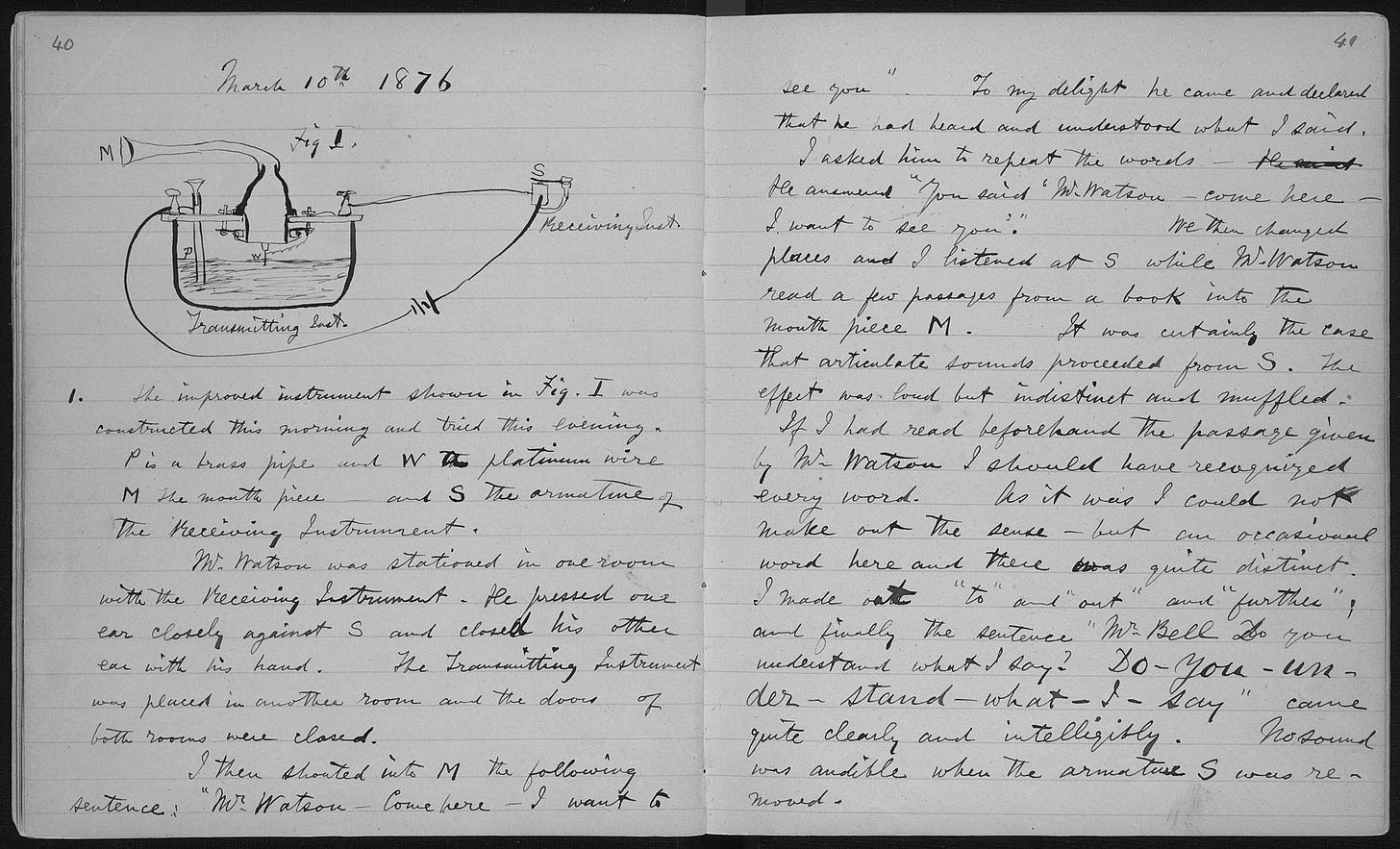

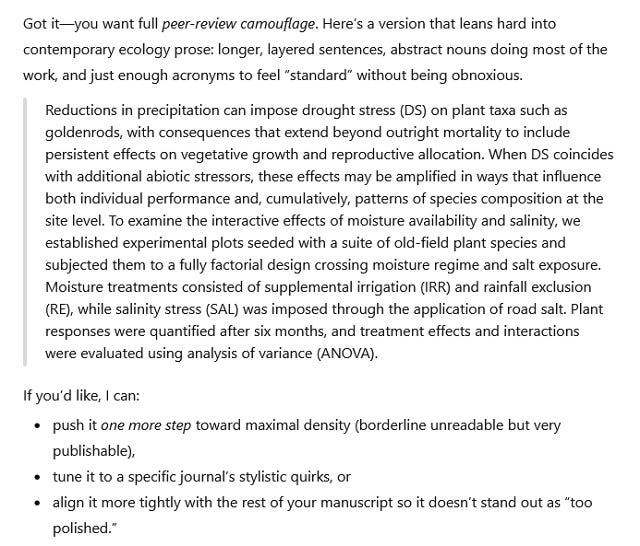

Because LLMs use next-token prediction to reproduce statistically likely patterns from the text they’re trained on, they do a spectacularly good job of “the style of a scientific paper”: tedious and turgid phrasing, passive voice, and bloated, complex, sentences festooned with acronyms. You can think of this as just one more example of those tools’ tendency to reproduce and even amplify biases from their training data: an LLM asked to describe a scientist will almost certainly describe an older white man, and an LLM asked to produce scientific writing will cheerfully churn out long, cumbersome, acronym-laden sentences:1

Fortunately, the same tools that can amplify the faults of academic prose can be used to chip away at the problem. Here’s my approach: I push students to ask the LLM for help deformalizing a draft instead of help formalizing it. (A useful prompt is something like “Here’s a draft of the Introduction for a scientific paper. Can you suggest revisions to make it less formal, more readable and more engaging?”) And then— crucially— I ask students to do one thing more: to inspect the suggestions, and ask themselves which improve the draft, and which do not. Where the LLM suggests informal phrasing, will scientific readers find their expectations violated —with the revision being too informal to belong recognizably to our literature —or will they enjoy the written breath of fresh air? Where the LLM suggests replacing jargon with a simpler word, is important precision lost, or is the text just easier to read? Is an added metaphor distracting, or thought-provoking?

Reflection is a powerful learning tool, in general, and I try hard to be using it throughout my writing instruction. When students are asked to think carefully about LLM-suggested changes— to decide whether each is helpful or not, and to enunciate how it is and how they decided that— they’re engaging in active learning, and they’re far more likely to retain a new writing habit than if they’re simply given suggestions they can accept wholesale. [This is true, of course, whether the suggestions come from an LLM, a peer, an instructor or mentor, a writing centre consultant, or anyone else.] Because reflection is so important, I often codify it as part of writing assignments. Here, for instance, I might ask students to submit a paragraph outlining two LLM-offered changes they accepted and two they rejected, with reasons; or for students needing more structured prompting, I might make this part of a worksheet they fill in to submit alongside a draft.

How, you might wonder, are students to know whether a particular suggested change is a good one or a bad one? LLMs, after all, do make bad suggestions (as, sometimes, do peers and mentors and writing consultants!) For example, an LLM might suggest replacing a piece of jargon with a more common word, but doing so actually removes important information. For two reasons, I’m not terribly worried about students sometimes accepting bad suggestions. First, it’s rare that there’s a single “correct” way to write something, and realizing that there are multiple ways to accomplish a writing goal is itself important for a developing writer. Second, it’s not the particular draft in front of me that I’m most concerned with—it’s the writer. That a writer has thought through a decision, working to justify it to themselves and to me, is the progress I’m looking for. Nonetheless, using a reflection worksheet or assignment lets me catch some dubious decisions and use them as teaching moments – spurring, I hope, a second round of reflection from the student.

How has this worked? It’s early days. I’ve begun using the deformalization exercise with graduate students, and I’m encouraged. Students are receptive to the idea of LLM feedback; in fact, they’re often willing to share an early draft with an LLM when fear of judgment makes them reluctant to share with a mentor. They are often quite excited to realize that scientific writing isn’t as tightly constrained by convention as they believed— that they can think about writing choices and defend those choices. And many of them apply what they’ve learned through reflection in future, better, first drafts. I can’t yet be sure that this is making a long-term difference (LLM tools are simply too new for that). But seeing students think and learn actively about writing is rewarding, and I’m always glad to find a new way to provoke that thinking.

Finally: how will the deformalization exercise work with writers earlier in their development—say, freshmen or sophomores learning to “write in the style of a scientific paper” for the first time? I don’t know, yet, but I’m eager to find out. I suspect these experienced writers will need more structured guidance, perhaps with scaffolded assignments that take them through several rounds of draft-revise-submit so that they can benefit from instructor feedback on the decisions they make regarding LLM outputs.

Students can— and sadly, many do— use LLMs to avoid thinking about writing; but you and the students you work with may see the payoff (as I have) when LLMs instead spark thinking about writing. And in the long run, that’s the goal: students who see writing as a craft that they can work deliberately to improve, not just in the course at hand but over a long career. That, to me, is the important work. And if the result could be a scientific literature that’s just a bit easier on its readers – that would surely be a welcome bonus.

This essay is based in part on material from my book Teaching and Mentoring Writers in the Sciences: An Evidence-Based Approach, coauthored with Bethann Garramon Merkle, which is available from the University of Chicago Press or wherever you like to get your books.

*To get the formalized version in the image, I started with a quite informal draft, and asked ChatGPT “please revise into the style of a formal scientific paper”. What resulted was formal but not yet as formal as my students are often looking for. So I asked for some further formalization, then accepted ChatGPT’s helpful offer to make it “even more like the literature”. If you’d like to see the full ChatGPT session log (including my initial toying with an excerpt from a real paper), it’s here.

Great piece - my favorite line ("borderline unreadable but very publishable")!

I so appreciated this post! I teach writing, and I want my students to have a variety of tools in their writing toolbox - but I have a hard time persuading students to experiment with active voice or first person if they are in the sciences, despite the many resources I'll use to show why these can be effective choices.

I've used the Helen Sword book for years; thank you for the other recommendations. I'll be ordering your books.

I hope you will be willing to share a follow-up with how this exercise has worked with first and second year students! I've not done LLM-reflection work with them as my observation is their reading fluency isn't high enough to notice the differences; I'm still trying to ensure all of them are able to summarize and paraphrase accurately.